Fantastic Fest Part the Second: The Creator, River, Concrete Utopia, Stopmotion, and Dream Scenario

The second of two dispatches from Austin.

Here’s a minor miracle: seeing 20 movies at a film festival and only actively disliking one of them. That would be Pet Sematary: Bloodlines, one of three movies I reviewed for Variety alongside The Toxic Avenger and the infinitely superior Strange Darling. With equal emphasis on world premieres, highlights from the year’s major festivals, and its patented secret screenings, the program came together with a chaotic elegance wholly befitting this genre-centric celebration. Following my first dispatch, here are five more movies I felt compelled to write about:

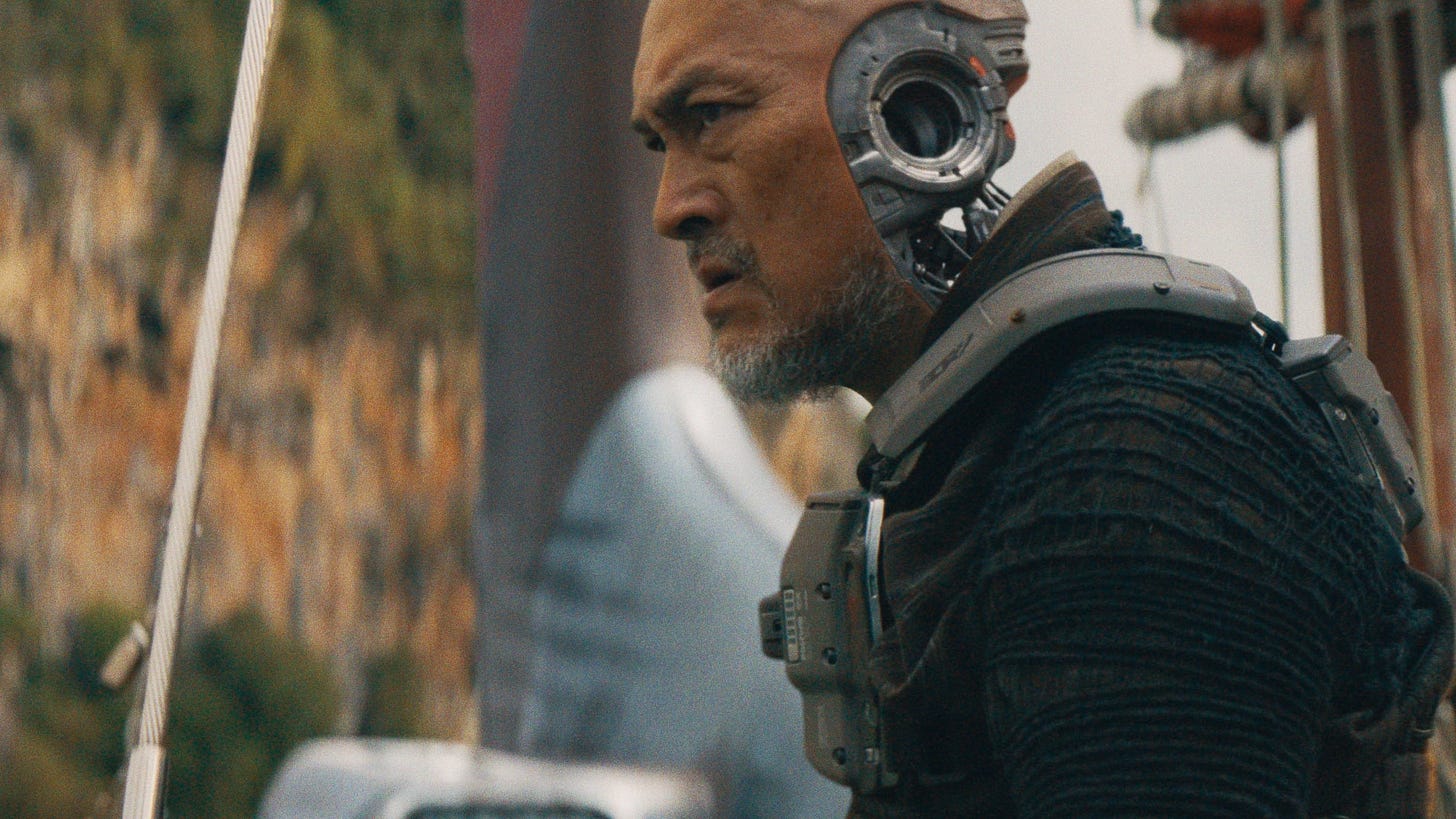

If ChatGPT and Midjourney are any indication, the AI takeover won’t be nearly as dramatic as it is in The Creator. What we’ve seen so far has been pernicious, but also deeply boring — a lot of soulless art and poorly written articles about high-school football games. All things being equal, Godzilla director Gareth Edwards’ long-awaited followup to Rogue One might be preferable. A few decades from now, the artificial intelligence designed to protect humanity instead goes full Skynet and nukes Los Angeles, prompting the western world to ban it. The Republic of New Asia has not, however, and so the two sides are at war with one another. What follows is deeply derivative — a little bit of Terminator’s unlikely savior narrative, several Inception-style dead-wife flashbacks — but just as deeply compelling. Part of that is due to a pair of exceptional performances from John David Washington and especially first-time child actor Madeleine Yuna Voyles, but mostly it’s thanks to how stunning it looks. Filmed in Thailand and sporting a near-future aesthetic in which the technology is more workmanlike than glamorous, the visuals are consistently arresting. When people bemoan the lack of new projects in Hollywood, which loves producing sequels and reboots more than some people love their own children, The Creator is exactly the kind of movie they’re missing. The ideas here are familiar, but they’re also well considered. It might be my favorite sci-fi epic in years.

I hope there isn’t a sequel.

It might sound like faint praise to call River an instant classic in the time-loop canon, given how few movies are actually part of that particular genre, but Junta Yamaguchi’s lighthearted charmer is a worthy complement to the likes of Groundhog Day all the same. Confining the action to just two repeating minutes rather than a 24-hour span allows the entire movie to take place in (un)real time; it also forces Yamaguchi and screenwriter Makoto Ueda to be clever on their feet for the entirety, a tricky task they make look effortless. Set at a Japanese ryokan you’ll wish you could book for an indefinite stay of your own, River distinguishes itself in part by how cheerful it is — a function of the fact that the main characters are all employees of the inn more concerned with comforting their guests than they are with themselves. (One character does kill himself during one of the loops, as Bill Murray does many times in Groundhog Day, but not because he can’t take it anymore — he just wants to see what it’s like.) Everyone responds to the situation with equanimity, which in theory could make the film feel low-stakes but in practice just makes it an unusually enjoyable crowdpleaser. It’s also gorgeous, with soft-focus cinematography capturing the idyllic setting as few other approaches can. River is ultimately a love story between two of the ryokan’s employees, and for one brief stretch functions as an uplifting inverse of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind — and one you won’t want to forget.

A disaster movie in which the true catastrophe is what happens to society afterward, Concrete Utopia begins with a brief glimpse of a world-historic earthquake leveling Seoul and only gets more desperate from there. When the Hwang Gung apartment complex is the only one left standing for miles in every direction, what’s left of the city is instantly divided into two groups: those who live there and those who do not. The former have always been here and deserve everything they have, their thinking goes, while the latter are parasites living off the kindness of strangers. (After initially referring to them merely as outsiders, they even take to calling them cockroaches.) South Korea’s Oscar entry, which was directed by Um Twae-ha and proves worthy of its awards-season honor, isn’t subtle in its class-conscious plotting, but this has never been a genre known for its subtlety. Complicating matters further is the fact that many of the refugees are former residents of the more luxurious complex across the street; in the before times, they looked down on the very people they now look to for help. In the vote to decide their fate, those on the “evict” side win in a landslide. A well-run if vaguely authoritarian system emerges complete with an Anti-Crime Force, turning Hwang Gung into a largely self-sufficient ecosystem — at least until the days inevitably grow colder and resources grow scarcer. “Can’t people just be humane, peace-loving citizens?” asks one of the more well-meaning survivors. If they could, movies like this wouldn’t exist.

“Great artists always put themselves into their work,” says a creepy little girl who may or may not be real in Stopmotion. It’s rare for a film-within-a-film to be compelling in its own right, but Robert Morgan’s gruesome feature suffers from the opposite problem: the animated oddity being slaved over by Ella (Aisling Franciosi) is so artfully disturbing that you may find yourself more intrigued by it than you are by Stopmotion itself. It isn’t long before you begin to wonder how much of what’s happening is “real” in the truest sense of the word as the struggling animator starts taking direction from said moppet, much to the chagrin of her ailing mother and increasingly concerned boyfriend, but it is a long time before you actually find out. (In general, assuming that anything truly bizarre is part of Ella’s descent into madness as she tries to finish her film is probably a safe bet.) The puppets she creates are truly horrific, like stomach-turning creations born of mortician’s wax and animal flesh; you’ll wonder who dreamt up something so ghastly even as you find yourself wishing for a longer glimpse of them. There’s more than one way to be consumed by your work, and Stopmotion explores damn near all of them with varying levels of success.

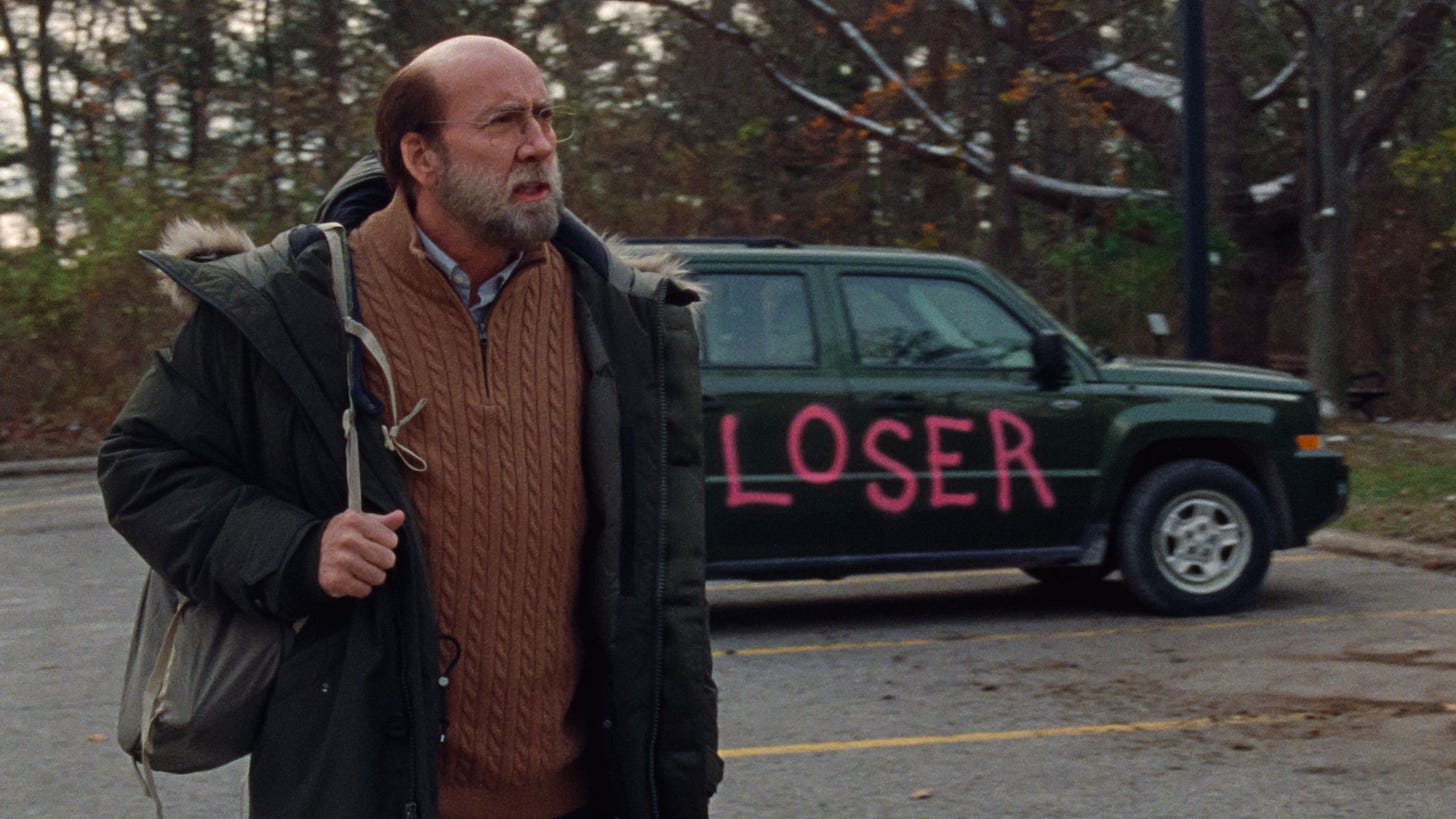

Nicolas Cage has been in the joke for some time now, and his leaning-into-it era has been among the most fruitful of his entire career. That’s saying a lot, given the sheer volume of singular performances he’s turned in over the last 40 years. Movies like The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent, Renfield, and now Kristoffer Borgli’s Dream Scenario have been almost self-reflexive in the extent to which they’ve nodded toward their star’s meme status; here especially, it’s impossible to imagine anyone else in the lead role. That would be Paul Matthews, an unremarkable professor who becomes a literal overnight sensation for the oddest of reasons: millions of people start dreaming about him at the same time. At first it’s a viral novelty, if also an inexplicable one, but when the dreams take a violent turn the film turns into a feature-length version of Mr. White’s proclamation from the first scene of Reservoir Dogs: “You shoot me in a dream, you better wake up and apologize.” Dream Scenario comes dangerously close to losing his way once it veers into cancel culture/milkshake duck territory, ultimately saving itself on the strength of Cage’s performance and a wonderfully sad final sequence. We may not remember how our dreams begin, but when we’re lucky we remember how they end.